Restoring Trust in the Heart of PA’s Political Realignment

One of the defining features of late 20th and early 21st century American politics is the loss of faith in our institutions. A recent poll in U.S. News shows that 85% of Americans say “government officials and other community leaders care more about their own power and influence than what’s best for the people they represent.” While government officials fare particularly poorly, supermajorities of Americans express disappointment with health care leaders, business leaders, and education leaders. It is safe to say there is across-the-board disenchantment with our institutions – not just with the government.

It wasn’t always this way. While it’s easy – and at times dangerous – to wax nostalgic about the past, there was a time when Americans expressed far greater trust in government and corporate opinions. In 1966, researchers found that almost 80% of Americans thought that they could trust the government in Washington to do the right thing “most of the time” or “just about always.” Over 60% of Americans believed that the government was being run for the benefit of all, and 70% believed that “not many” or “hardly any” of the people running the government in Washington could fairly be described as “crooked.”

While having some skepticism about the government’s intentions or abilities may be healthy for a democracy, it seems likely that these astronomical levels of distrust make democracy difficult to sustain. If government’s authority derives from the consent of the governed, but the governed view the ones governing them as untrustworthy, that consent becomes more tenuous. But given that things were not always this way, there is cause for hope that there can be an end to them.

To better understand this shift in Americans’ faith in both their government and their society, RealClear Opinion Research has partnered with Emerson Polling, through a generous grant from The Heinz Endowments, to produce high quality, large-sample polls of residents of southwestern Pennsylvania.

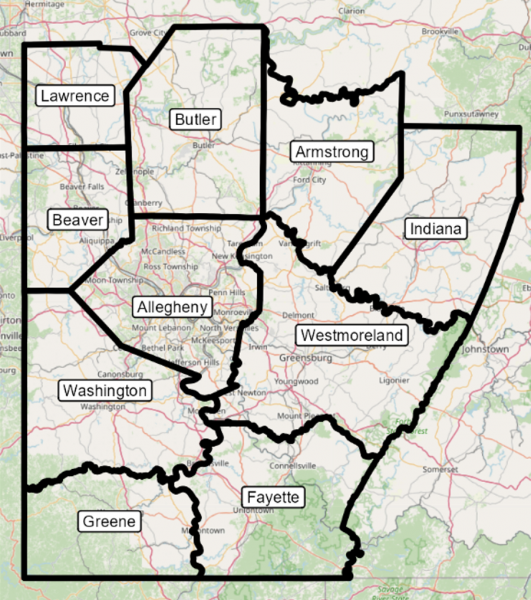

Our series will focus on ten counties in southwestern Pennsylvania: Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Fayette, Greene, Indiana, Lawrence, Washington, and Westmoreland. They are depicted in the following map:

We chose to focus on a particular region because most investigations into trust are conducted at the national level. This can obscure important, granular-level details that may occur at the local level. The reasons a Hispanic resident of downtown Los Angeles may distrust the government, for example, could be different from the reasons that a rural resident of Pennsylvania’s Greene County may distrust the government.

As for why we chose these counties, we did so for several reasons. First, this is a remarkably diverse region, combining a major metropolitan center with suburban and even rural counties. Allegheny County is centered on the city of Pittsburgh and its inner suburbs. It combines an old industrial city that has experienced ongoing urban renewal with old-line and sprawling newer suburbs.

Butler County is the wealthiest county in the region, with a median household income approaching six figures. Like Allegheny’s neighboring counties – Westmoreland and Beaver – it faces challenges in accommodating population growth and commuters while still serving a substantial rural population. Meanwhile, Washington County mixes suburban growth and renewal with an old industrial base and rural areas in the south.

Finally, our sample includes a few counties that are largely a mixture of rural and small-town settings. Greene and Fayette counties are of particular interest, as they are in the heart of Pennsylvania’s Appalachia; Fayette County persistently reports one of the state’s lowest household incomes and among its highest unemployment rates. By employing a unique, large-sample survey in the region, we can explore differences in trust in different contexts while controlling for the overall region.

Second, the challenges residents experience here exemplify those faced across the nation. Residents of Allegheny County search for affordable housing and scramble to make ends meet in an increasingly expensive Pittsburgh. Unemployment remains a persistent problem, yet while the city seeks to bring in new jobs by reinventing itself as a tech/AI hub, a decades-long decline in the county’s population strains the very tax base needed to provide new infrastructure. Meanwhile, the county’s suburban and exurban residents also need infrastructure improvements for travel to the city.

Rural residents express concerns about transportation but also face particular challenges as younger residents leave for seemingly greener pastures beyond the region; local news sources evaporate; and jobs become increasingly hard to find. In recent years, rural colleges in Pennsylvania have faced funding challenges, consolidating or even shutting down. Housing affordability has become an issue here, as corporations increasingly buy land and houses in scenic places like Fayette County, driving up home prices and property taxes. All these problems can affect an individual’s belief that the government is functioning well, as well as one’s ability to trust society as a whole.

Finally, RealClearPolitics is, of course, a political website, so it should be unsurprising that there is a political angle. This region is home to one of the most remarkable political shifts in recent American political history.

For most of the post-New Deal era, this part of Pennsylvania was one of the most reliably Democratic areas of the U.S. In 1988, Michael Dukakis won almost 60% of the two-party vote (that is, excluding third parties) in the region. In 1992 and 1996, Bill Clinton won 63.2% and 56.5% of that vote. But the Democratic vote share in the area would decline in every subsequent election, until Hillary Clinton won just 46.4% of the vote in 2016. Joe Biden fared slightly better, with 47.7% of the vote – enough to enable him to narrowly carry the state – but Kamala Harris’ vote share dropped again to 47%.

Even this doesn’t tell the entire story, because the Democratic vote share in Allegheny County, the most populous county in the region, has remained remarkably stable over time. Dukakis won 60.1% of the vote there, while Harris won 60.2%. In every other county, Harris ran at least ten points behind Michael Dukakis. This is all the more jarring, given that Harris nearly won the national popular vote, while Dukakis lost it handily. The shifts range from a 10.8 percentage point shift in Butler County to an astonishing 38 percentage point shift in Greene County (Dukakis won 65.2% of the vote, Bill Clinton won 70.8%, Harris won 27.2%).

In other words, this region is ground zero for the populist shift toward Republicans that we’ve witnessed in the past several decades, and that accelerated in the last decade. Much has been written about Donald Trump’s ability to harness individuals’ lack of faith in government and concerns about the direction of civil society. By looking at determinants of social trust here, we will be better able to understand the most consequential political developments of our time.

We do wish to emphasize that our goal is not to chide or castigate voters for their low levels of trust or their voting habits. This will not be “What’s the Matter With West Finley.” We will attempt to meet these residents where they are and to understand their viewpoints rather than to criticize them. This project is meant as much to give political leaders insight into how they can regain trust as it is to look at ways where the individual residents’ viewpoints may be in tension with reality.

We hope you look forward to watching our series unfold as we explore the attitudes of this unique region of America.